Electromagnetic Waves in Matter

The behavior of electromagnetic waves changes dramatically when they propagate through materials rather than vacuum. This interaction between light and matter underlies numerous phenomena in our daily lives, from the colors we see to modern optical technologies. Understanding these interactions requires bridging two perspectives: the microscopic view of how individual atoms respond to electromagnetic fields, and the macroscopic description of wave propagation through bulk materials.

Microscopic Picture of Dielectric Response

Single Atom Response

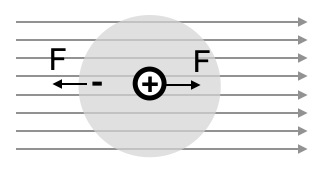

To understand how materials respond to electromagnetic waves, let’s first examine how individual atoms become polarized in an electric field. Our model atom consists of:

- An electron charge

- A positive nucleus at the center of this negative charge distribution

The charge density of the electron cloud is:

This configuration creates a radial electric field inside the cloud:

where

Atomic Polarizability

When we apply an external electric field

This force balance between the external field (pushing the nucleus) and the internal field (trying to restore the nucleus to the center) determines the atomic polarization, leading to the displacement:

This displacement creates a dipole moment:

The dipole moment increases linearly with the external field, with the proportionality constant:

known as the electronic polarizability. Note that this polarizability scales with atomic volume.

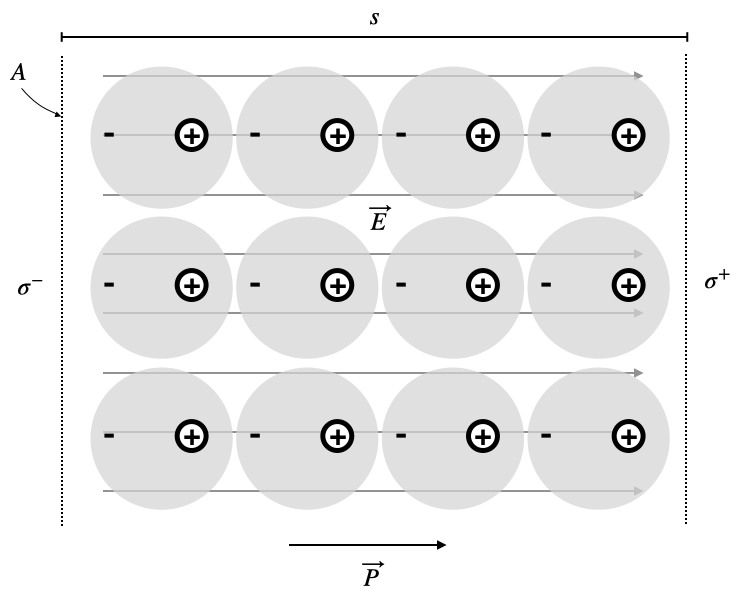

From Single Atoms to Collective Response

When many atoms in a material are exposed to an electric field, their individual dipole moments combine to create a macroscopic polarization. The collective behavior can be characterized by the polarization density:

where

In real materials, each atom experiences not only the external field but also the fields from neighboring dipoles. This leads us to consider the local field effects and the transition from microscopic to macroscopic descriptions, which we’ll explore in the next section.

Macroscopic Description of Dielectric Materials

Polarization Density and Surface Charges

The transition from microscopic to macroscopic behavior becomes apparent when we examine a sample of polarized material. For a cylindrical sample with cross-sectional area

This alignment leads to:

- Total dipole moment:

- End charges:

- Surface charge density:

More generally, the surface charge density at any boundary is:

where

Volume Charge Density

When polarization isn’t uniform throughout a material, we need to consider both surface and volume charges. All bound charges in the material must sum to zero since the material was initially neutral:

Using the surface charge relation

Applying Gauss’s theorem:

This leads to the local relationship:

This fundamental equation reveals that bound volume charges appear wherever the polarization has a divergence - that is, wherever it changes spatially in a way that creates an imbalance of positive and negative charges.

Electric Displacement Field

In materials, the electric field’s divergence must account for both free charges and bound charges:

Using

This suggests defining the electric displacement field:

which simplifies Gauss’s law to:

This is beautiful, since it brings back the same dependence on free charges as in vacuum, but now with the displacement field

Linear Dielectric Response

For many materials, the polarization density is proportional to the applied electric field:

where

The displacement field becomes:

with electric permittivity:

The dimensionless ratio:

is the relative permittivity or dielectric constant, though it typically depends on frequency.

Clausius-Mossotti Relation

In dense materials, the local electric field

where

The polarization density relates to the local field through:

Solving this equation and comparing with

This fundamental relation connects microscopic polarizability to macroscopic permittivity, accounting for local field effects in dense media.

Maxwell’s Equations in Matter

The presence of bound charges and currents in materials requires a modified form of Maxwell’s equations. The four fundamental equations become:

Faraday’s law remains unchanged, describing electromagnetic induction regardless of medium.

Gauss’s law now involves the displacement field

Ampère’s law includes both the displacement current

The absence of magnetic monopoles remains fundamental. The material properties enter through the constitutive relations:

Similar to electric polarization, materials respond to magnetic fields through magnetization

For linear magnetic materials:

where

Wave Propagation in Non-conducting Matter

For isotropic media without free charges (

where the phase velocity is:

For non-magnetic materials (

This fundamental relation connects our microscopic understanding of atomic polarization to the macroscopic phenomenon of light propagation. In a later section we will provide a more detailed discussion of the microscopic origins of the refractive index. Monochromatic waves in matter take the form:

The wavevector

When electromagnetic waves enter a material, their wavelength changes while the frequency remains constant. This is because:

where

Special Cases

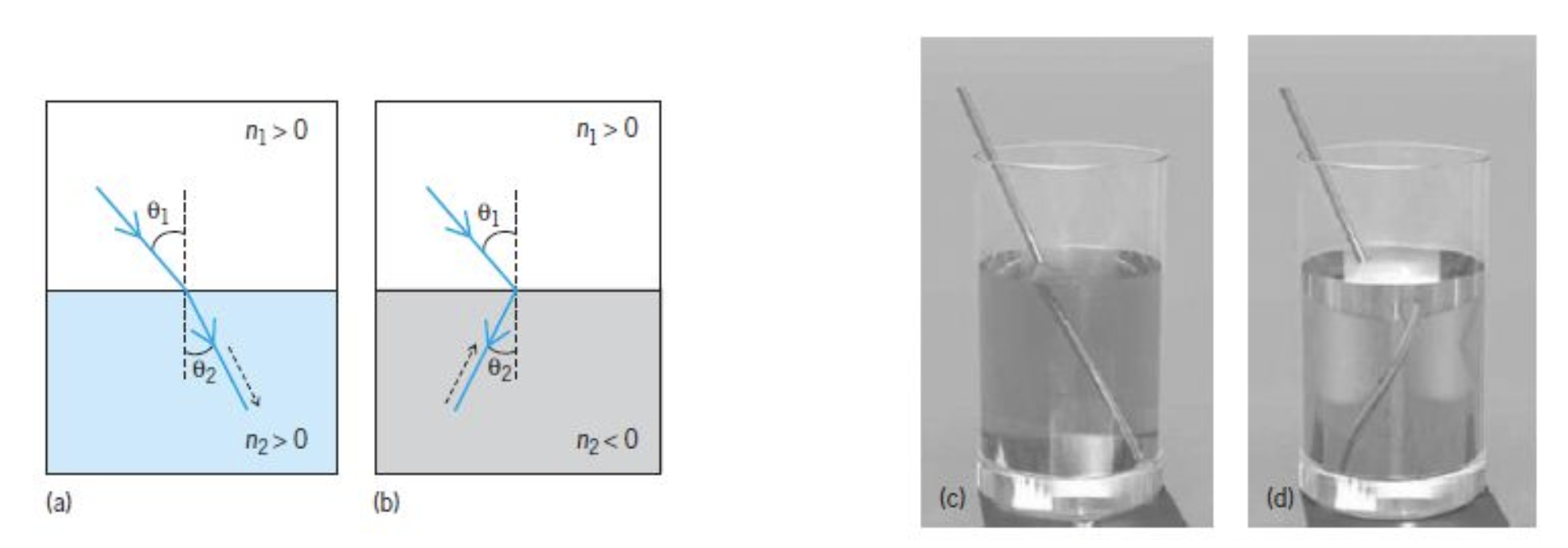

Negative Refraction

While most materials have

Energy Flow in Negative Index Materials

The Poynting vector describes energy flow in electromagnetic waves:

where

For a plane wave,

Using the vector triple product identity:

Since

In negative index materials (

This remarkable result shows that energy flows opposite to wave propagation, a unique characteristic of negative index materials.

Metamaterial Realization

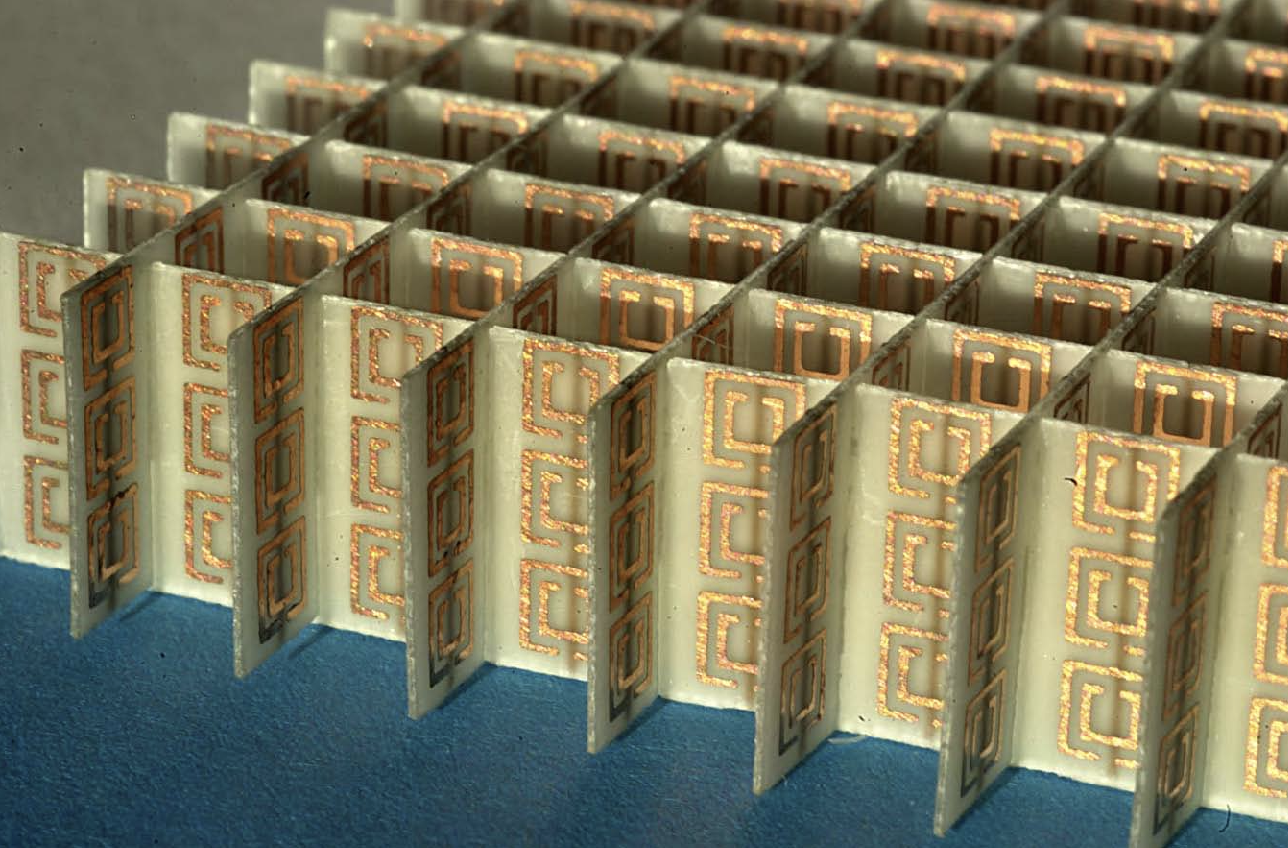

A split-ring resonator typically consists of a pair of concentric metallic rings, each with a gap. These rings can be thought of as forming an LC circuit, where the rings themselves provide the inductance (

Resonant Frequency of the SRR

The SRR behaves as an LC resonator with a specific resonant frequency (

where: -

Magnetic Response of the SRR

When an external alternating magnetic field is applied perpendicular to the plane of the SRR, it induces a circulating current around the rings. This induced current creates a magnetic dipole moment that opposes the change in the external magnetic field (Lenz’s Law).

Magnetic Susceptibility

The magnetic susceptibility (

where

Polarizability of the SRR

The polarizability

where: -

Effective Permeability

The effective permeability

Substituting

This equation describes the frequency-dependent effective permeability of a metamaterial containing split-ring resonators.

Negative Permeability

For negative permeability to occur, the term in the denominator

The final equation for the effective permeability of a metamaterial with split-ring resonators is:

Interpretation

- When

- The parameters

This equation highlights how the resonant properties of the SRRs lead to a negative permeability in the metamaterial, enabling unique electromagnetic properties such as a negative refractive index.

The concept of negative refractive index, first theorized by Victor Veselago in 1968, predicted materials with simultaneous negative permittivity and permeability would exhibit:

- Reversed Snell’s law

- Reversed Doppler effect

- Reversed Cherenkov radiation

Modern realizations use carefully designed structures with:

- Split-ring resonators for negative μ

- Wire arrays for negative ε

- Precise geometric arrangements to maintain wave propagation

These materials enable novel applications including:

- Superlenses breaking the diffraction limit

- Electromagnetic cloaking

- Novel waveguiding devices

The concept of negative refractive index was first theorized by Veselago (Veselago 1968). Later, Pendry showed how these materials could be used to create perfect lenses (Pendry 2000).